In modern conflict, the lines between organized crime, espionage, and cyber warfare are extremely blurred. In large part, this is because different nation-states’ cyber operations infrastructure is designed with innate plausible deniability. Another major factor is that many of the same tactics and “weapons” utilized in petty cybercrime are just as effective when engaging in cyber warfare. A rising threat actor in this space is the DPRK (North Korea). In the past decade, the authoritarian regime’s most famous cyber operations have been attributed to state sponsored entities collectively designated “Lazarus Group”. While often having varying success, Lazarus Group have a unique profile-with targets ranging from movie studios, to massive crypto wallets, to healthcare infrastructure.

Before getting started with this article, I just wanted to give credit to the massive amount of work done by investigative tech journalist, Geoff White. Without his extensive work, this article just wouldn’t be possible. Buy his books. Listen to his podcasts. Read his articles.

Since the 2011 ascension of North Korean dictator, Kim Jong-Un, the DPRK has rapidly made moves to increase its bargaining power on the international stage. Coinciding with well-publicized increased nuclear ambitions, there has also been a marked increase in activity from North Korean-affiliated hacking groups. While a solid timeline of DPRK cyber operations can be established since 2009, it was after the 2011 succession that the sophistication, intensity, and deliberate nature of the attacks increased. For a nation as disconnected from the global economy as the DPRK, this shift makes sense. Cyber operations are an extremely cost-effective way to exact influence and control through espionage and deterrence. Being a threat actor with a very specific agenda, the targets and goals of DPRK state-affiliated hackers tend to highlight a very tracible pattern of culpability and come with highly recognizable toolkits. While several names have been given to North Korea’s hacking groups, including Hidden Cobra, Zinc, or Whois Team, the name most commonly associated with North Korea’s cyber criminals is Lazarus Group.

“North Korea is a formidable cyber power, standing alongside major players like the United States, China, Russia, the United Kingdom, Israel and Iran.”

Carolina Polito, Chong Woo Kim

The Asan Institute for Policy Studies

Who Are They?

A question that many journalists ask when confronted with the extent of the DPRK’s cyber operations is, “how does a country that barely has access to the internet develop such a robust cyber warfare program?” Infrastructure is incredibly under developed. Use of the internet and communication with the outside world is all but illegal. The entire country formally only has a range of 1,024 IP addresses.

While this is a natural question to ask, a 2019 estimate by The Asan Institute actually has the number of North Korea’s cyber operators at 7000.

How can this be? Who are these cyber soldiers? How do they get their training?

“[they are] Warriors… for the construction of a strong and prosperous nation.”

Kim Jong-Un 2013 address to the RGB

While it may appear counterintuitive at first, the country’s lack of connection to the outside world, and the harsh control of its government could provide the unique boons that their cyber operators require. The only people who have access to the internet are associated with the government, allowing them to shape their soldiers strictly to the military’s needs. There is also little need to be clean about the work that they do: the DPRK doesn’t have a lot to lose if detected, and their agents will never be extradited to see a foreign court. North Korea’s reliance on China for much of its IT equipment allows it to hide many of its activities behind Chinese access points and IP addresses, which creates a number of issues when accurately attributing incidents to DPRK-based threat actors.

Potential recruits are nurtured from the tops of their classes in math and science high schools and then filtered into several universities that focus on cyber operations training with courses in networking and advanced computer programming. Kim Chaek University of Technology, Kim Il Sung University, and Mirim College in Pyeongyang are all among those utilized for this purpose.

The curriculum at these universities is supposed to take five years to complete, with a three year research period afterwards. This is described as a process being similar to earning a Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in these IT-related fields. Many of these graduates conduct their research in neighboring countries through the Pyeongyang Information Center, and have a reputation for being world-class programmers.

One could safely speculate that this career path likely has broad appeal for young North Koreans, ensuring an increasingly rare opportunity to work predominantly in overseas roles, access the most advanced technologies, and achieve a high standard of living.

The Criminal Element

While there’s nothing inherently incriminating about simply having soldiers that are trained in information technology, North Korea is the only nation who seems to have developed its cyber program with outright theft as one of their major operations. In December of 2021, it was estimated that the DPRK’s cyber operators had already pilfered $2.3 billion through illicit activities. In 2020, proceeds from cyber crime made up 8% of North Korea’s GDP.

“North Korea’s operatives, using keyboards rather than guns, stealing digital wallets of cryptocurrency instead of sacks of cash, are the world’s leading bank robbers…”

John C. Demers, Assistant Attorney General (US)

In February of 2021, the United States’ FBI specifically named three individuals as hackers associated with Lazarus group. Park Jin Hyok, Kim Il, and Jon Chang Hyok are all accused of largely financially-based crimes while engaging in activities falling under the purview of Lazarus Group. The FBI report claims that the three men are all under the umbrella of the DPRK’s Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB)-an established intelligence agency. If the findings are true, this would mean that their activities are indeed sanctioned by North Korea’s government.

Verifiably involved in the Bangladesh Bank Heist, Park Jin Hyok worked with Chosun Expo Joint Venture, a front company for North Korea’s intelligence activities. Initially started as a joint venture between North and South to be a Korean language e-commerce platform, the South divested from the project. Chosun Expo has, throughout its history, masked itself as an online store, an online gambling site, a cryptocurrency exchange, and other ventures. Park was hired by the company as a gaming software developer in 2002.

While Chosun Expo is technically based in China, the FBI’s findings indicate that the site’s accounts are accessed from North Korea. It was when accessing these accounts that they were able to ascertain Park’s true identity.

The DPRK has claimed that Park is a “non-existent entity”.

Kim Il is another suspected Lazarus Group member that seems to have focused more of his effort into the cryptocurrency space. He has been known as Julien Kim and Tony Walker in these spaces, and claimed to have been operating out of Russia, Singapore, and China.

Kim Il has been most famously associated with Marine Chain. The project was pitched as a blockchain platform that allowed users to exchange digital tokens for shares of shipping vessels. The Initial Coin Offering (ICO) was registered on 12 April 2018 in Hong Kong, and Il, under the alias of Tony Walker, tried to drum up excitement for his seemingly novel idea. However, suspicious Reddit users flagged Marine Chain’s website for being an almost complete ripoff of the project on shipowner.io. This was the beginning of the broader crypto world becoming aware of Kim Il’s activities.

Among the assertions from the FBI’s reports are claims that Kim Il has personally developed malicious cryptocurrency software. Among the apps allegedly developed were crypto wallets, fake crypto exchanges, mining software, portfolio management software, price tracking software, and price forecasting applications. Also accused of being involved in the development of these malicious cryptocurrency applications is Jon Chang Hyok, of whom few details were released.

An Infamous Close Encounter

A common social engineering tactic that potential threat actors will use is applying for a job through faked credentials and assumed identities. In the most extreme cases, there’s a chance that the attacker can actually infiltrate an organization. However, there is some information that can be ascertained through the job seeking process that may be of value. For instance: if a job posting asks for expertise in a set of programming languages, or experience with specific server architecture or operating systems, this can save an attacker a lot of time in the development of a new tool.

No bullshit, I think I just interviewed a North Korean hacker.

Jon Wu Aztec Network

In a job interview situation, the threat actor can even try to direct the conversation in a way that it can provide even more information than the job posting, without the interviewer even realizing it. This is one of the possibilities Jon Wu of Aztec Network describes in his now infamous encounter with “Bobby Sierra”-a man he believes was an assumed identity for a DPRK hacker.

In the account, Wu describes a number of disqualifying behaviors and red flags during an interview over Zoom. This included “Bobby” insisting on having his camera off, and going completely silent for five minutes when asked about his previous occupation.

At the end of the thread, Wu says that no matter how much North Korean hackers may improve their tactics and basic skills, “Thankfully, they can’t fix how fucking out of touch and incompetent they are.“

Despite Wu’s claim that the hackers of the DPRK are incompetent, their history of incredibly successful campaigns of espionage and theft would beg to differ.

An Ambitious History

A major “tell” of North Korean cyber operations has historically been their correlation with North Korean nuclear tests or the introduction of relevant international policies. However, as the needs and capabilities of North Korea grow, the role of Lazarus Group has evolved to cover more strategic territory than probing attacks and intelligence operations against mostly the Untied States and South Korea.

Operation Troy – 2009

July of 2009 marked the beginning of a series of attacks against South Korea that would continue through 2013 in several waves. On the surface, the attacks utilized a botnet which propagated through a series of South Korean IRC servers. It was found to have infected devices numbering from between 20 and 166 thousand. These incidents remained relatively untraceable, written in Korean, targeted only at South Korea. The depth of their infiltration went undetected over a long period of time-what’s known as an Advanced Persistent Threat. In their response whitepaper, McAfee Labs considered this particular APT not only a cyber attack, but a covert espionage campaign.

As an APT, Operation Troy utilized trojan horse malware that attached itself to systems owned by South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, National Assembly, Ministry of Public Administration and Security, and a number of large corporations in both the banking and media sectors. This malware established a massive network of compromised devices that could be used for intelligence gathering and DDoS attacks. Tools Used: My.doom, Trojan.Dozer Further Reading: Z:\MAKE TROY\, NOT WAR: CASE STUDY OF THE WIPER APT IN KOREA, AND BEYOND

Dark Seoul – 2013

March 20th, 2013 was the date of the so-called “Dark Seoul” incident. The botnet assembled over the previous four years went into full gear, launching DDoS attacks on a reported 32,000 devices. These devices, mostly stationed within South Korea’s financial services, had their hard drives overwritten and largely destroyed. Damage estimates were as high as $750 million. Tools Used: Trojan.Castov, Trojan.Castdos, Infostealer.Castov Further Reading: Four Years of DarkSeoul Cyberattacks Against South Korea Continue on Anniversary of Korean War

Operation Blockbuster – 2014

Operation Blockbuster was the moniker given to the joint-investigation into the 2014 Sony hacks. The hacks, which were conducted by North Korean actors, were in response to Sony’s release of The Interview, a film starring Seth Rogen and James Franco that portrayed American journalists assassinating Kim Jong-Un. The film also lampoons the control the Kim dynasty have had on the North Korean people, and has been used as a tool in the propaganda war between the two Koreas.

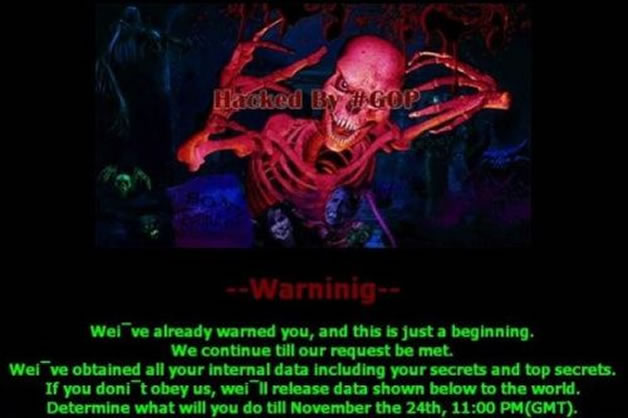

The attack was characterized by a type of malware that the researchers of Operation Blockbuster designated “WhiskeyAlfa”, which was found to have traces of previous tools used by Lazarus Group. During this particular attack, the group assumed the identity, the “Guardians of Peace (GOP)”.

Hundreds of Sony Pictures Entertainment employees showed up to work to find a screen with a rather dramatic red skeleton warning the company of a pending leak, unless a November 24th deadline was met in deciding whether or not the film would air. Systems were taken offline, and a massive amount of sensitive data was released to the public, including incriminating email conversations, unreleased films, login credentials, and hardware information vital to network infrastructure for Sony Pictures Entertainment and their film studios.

Tools Used: Brambul, Joanap Further Reading: HIDDEN COBRA – Joanap Backdoor Trojan and Brambul Server Message Block Worm

The Bangladesh Bank Heist – 2016

In 2016, North Korean hackers attempted to steal over a billion dollars from the national bank of Bangladesh. This particular story is the focus of the aforementioned BBC podcast featuring Geoff White, and is allegedly the single largest attempt by a state actor to steal funds from another nation to date.

It is believed that DPRK-aligned infiltrators were able to get into the bank’s network, and send instructions through connections established by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT). The orders attempted to transfer the money from Bangladesh’s Federal Reserve Bank account in New York City. The attack was executed during a time of day where the employees in New York would not be at work, and be less likely to react quickly. As well, according to the BBC, a printer with concerned communications coming from New York had been disabled. Tools Used: Insider threat/infiltration, mstouc.exe Further Reading: TWO BYTES TO $951M

Attacks On Polish And Mexican Banks – 2017

In Febuary 2017, Polish banks had been sustaining multiple attacks to critical network infrastructure. Poland’s SWOZ internal banking alert system was quick to publish a list of impacted IP addresses, but the damage was already extensive. A number of the impacted IP ranges were also prominently associated with banks in Mexico, and some in two dozen other countries. The government’s Financial Supervision Authority, a regulatory body for establishing security standards for the Polish financial sector, found themselves victim to a Denial of Service attack while Poland’s banks were reeling from the disruption.

Further investigation found malicious code injected as early as October of the previous year, and was traced to a malware known as Downloader.RATANKBA Ratankba, despite being written in Cyrillic, holds many similarities to tools utilized by Lazarus Group. Tools Used: Downloader.RATANKBA, TROJ_RATANBANKBA Further Reading: RATANKBA: Delving into Large-scale Watering Holes

WannaCry – 2017

While it was overshadowed in 2017 in the public consciousness by the more damaging NotPetya, WannaCry was one of a family of ransomware worms that utilized the EternalBlue exploit to devastating effect. EternalBlue is a cyberweapon that was leaked from the US National Security Agency designed to attack older Windows systems.

WannaCry is a ransomware worm that works by spreading to different computers through vulnerable SMB connections-often networked printers. Once it has infected a machine and propagated, it will encrypt the entirety of the infected machine’s file system and demand a “ransom” (typically money or cryptocurrency) in order to get the decryption key. In WannaCry’s case, it was a modest $300 in Bitcoin. However, often in these attacks, the victims don’t receive the decryption keys when they pay. It is an extremely efficient way to effectively destroy a large amount of property quickly while potentially funneling some hard-to-trace money on the side.

According to SophosLabs, the first confirmed WannaCry infections were detected in India, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. In a matter of days, it had spread to over 200,000 devices in 150 countries. Four days after the initial infection was detected, the BitCoin wallets linked to the ransom had received 253 payments, totaling about $71,647 at the time, but the ransom pay-outs were not the worst part of the attack.

Ransomware worms such as WannaCry are often the weapon of choice when launching attacks against civilian and governmental infrastructure. They’re highly adaptable and can be packaged with any number of exploits. As an example of infrastructure that was taken down in the attack, in the UK, 48 National Health Service trusts had been taken offline.

The estimated total damage caused by the attack was up to $4 Billion.

While many experts at first said that the attack, while damaging, seemed extremely unrefined and amateurish in execution, the UK, Canada, and the US were quick to blame North Korea. It was asserted that much of this was based on more traditional forms of intelligence. Tools Used: EternalBlue, Trojan.Ransom.WannaCryptor Further Reading: WannaCry explained: A perfect ransomware storm

Turkish Bankshot – 2018

In February of 2018, Turkey’s financial sector found itself to be the victim of another attack by Lazarus Group. It began with a series of spear phishing emails that contained malware attached to a Word document. The email itself is a fake bitcoin distribution agreement.

By March third, the first two targets were confirmed to have been infected: major state-run organizations in Turkey’s financial regulation body. More breaches were found in three of Turkey’s banks.

The malware was quickly detected and attributed to Lazarus Group, as it had a reported 99 percent match to Bankshot, a malware first reported by the US’ Department of Homeland Security as being in the DPRK’s toolkit. It was discovered by South Korea’s Internet and Security Agency that Bankshot exploited a flaw in Adobe Flash Player in order to secure persistent backdoor access. Tools Used: Vulnerability cve-2018-4878, COPPERHEDGE Further Reading: Hidden Cobra Targets Turkish Financial Sector With New Bankshot Implant

Current Activities And Trajectory

COVID-19 research:

In 2020, there were a number of attacks on healthcare providers and vaccine manufacturers involved in the production of COVID-19 vaccines. According to Microsoft, among them were DPRK actors, posing as World Health Organization employees, phishing for account credentials.

Pfizer, specifically, had an attempt against it from an actor presumed to be Lazarus Group. The manufacturer did not release details, and the report was posted by South Korea’s National Intelligence Agency. According to the agency, the attacks were attempts to steal the vaccine outright, as well as other treatment technologies in development. It later came to light that DPRK affiliates attempted to breach at least nine vaccine manufacturers, including Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and Novavax Inc.

Attempts at information theft via cyber operations increased dramatically during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. While one may be sympathetic to this effort, South Korea’s National Intelligence Service asserted that it was more likely the DPRK was trying to sell the vaccine, rather than develop their own.

Cryptocurrency heists:

Since 2017, North Korea’s cyber operations have focused less on disrupting and stealing from the traditional banking sector, and more on taking crypto assets from victims around the world. Besides their inflation in value over the past several years, one of the biggest reasons why cryptocurrency wallets make for enticing targets to attackers is the fact that once the victim’s private key is acquired and their assets are stolen, there’s very little that can be done to recover them. The operators of Lazarus Group have devised a number of ways and honed their skills over the past five years to successfully target both users and the semi-legitimate exchanges for crypto currencies.

In 2017, South Korean crypto exchange, YouBit, was attacked and had over $20 million of its assets stolen in two separate breaches. In 2018, Bithumb, and Coinrail were raided for an additional $77 million worth of cryptocurrency. These attacks pale in comparison to the $530 million that they would go on to steal from Japanese exchange, Coincheck.

Stealing cryptocurrency has become increasingly important to the heavily-sanctioned North Korean government. As sanctions have severely damaged the country, acquiring ready access to cryptocurrency allows them to launder stolen money for their nuclear research program.

More recently, the US government issued Alert (AA22-108A), warning of heightened social engineering attacks utilized by Lazarus Group in order to target holders of large amounts of cryptocurrency through various Trojan Horse packages.

The cyber actors then use the applications to gain access to the victim’s computer, propagate malware across the victim’s network environment, and steal private keys or exploit other security gaps. These activities enable additional follow-on activities that initiate fraudulent blockchain transactions.

the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency

Cryptocurrency reserves allow North Korea to finance assets in countries that sanctions may otherwise prohibit the DPRK from operating in. A North Korean agent with access to millions of dollars in Bitcoin can, theoretically, make anonymous purchases almost anywhere on the planet.

It should also go without saying that the almost nonexistent oversight in the crypto space, on top of the country’s lack of extradition treaties mean that the operators of Lazarus Group can essentially steal everything they want with impunity. As long as this remains the case, and DPRK hackers are self aware enough to not cross the line into what could be construed as true acts of war, I see little reason to believe any of this will change.

More On Lazarus Group

- BBC’s The Lazarus Heist podcast

- Geoff White on Popular Front and Darknet Diaries addressing Lazarus Group

- Vice News Asia on North Korean Hackers’ successful theft of 1.3 billion dollars